There are plenty of pundits out there arguing that today’s record-high valuations in the stock market are validated by ultra-low interest rates (see Fed Model). The problem with this idea is it really only tells us how we got here. What investors should really care about is where we’re going and ultra-low interest rates are not at all bullish for future returns in the stock market.

In some respects, the idea that low rates should mean higher equity valuations makes perfect sense. If the 10-year treasury bond only pays 1.7% and the dividend yield on the S&P 500 is closer to 1.9% why wouldn’t I be more inclined to buy stocks? Good question! And this is probably why investors bid stocks up to astronomical valuations in the first place.

The major problem with this line of thinking is that it is backward-looking and it is no justification for valuations to remain high going forward. I’ll let Cliff Asness explain:

It is true that all-else-equal a falling discount rate raises the current price. All is not equal, though. If when inflation declines, future nominal cash flow from equities also falls, this can offset the effect of lower discount rates.

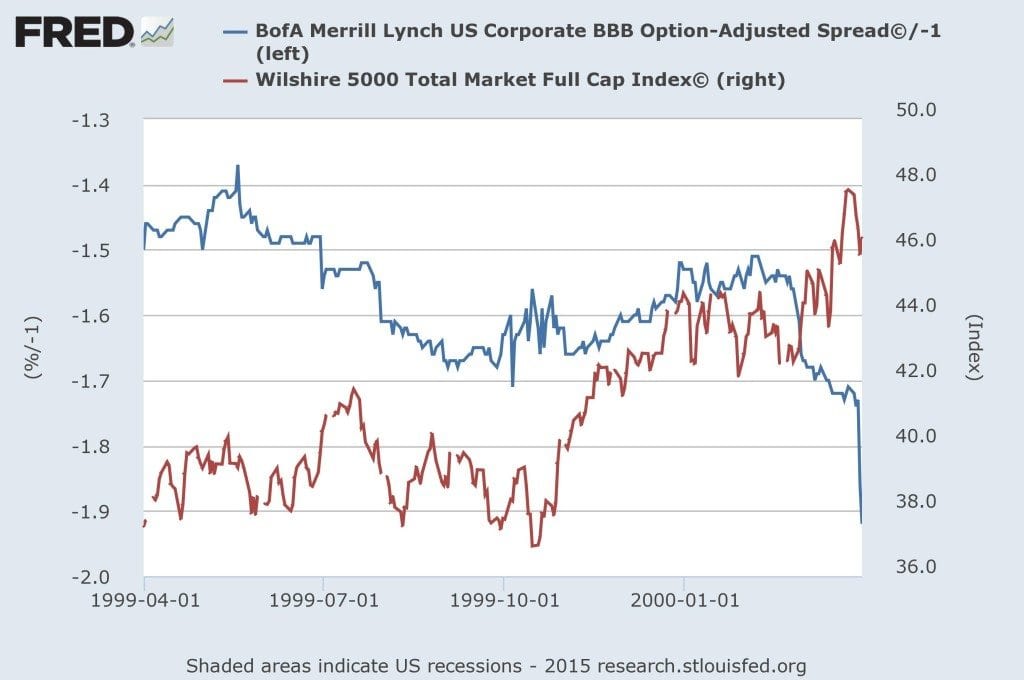

In fact, over time corporate earnings growth tracks very closely to the rate of inflation. This is why so many people like to say stocks are a good inflation hedge because they can typically raise prices to combat rising costs in an inflationary environment. But if that’s true then they also make a very poor deflation hedge as their earnings also must also fall when the rate of inflation does. And right now the bond market is pricing in the lowest levels of inflation since the financial crisis:

Chart via FRED

Chart via FRED

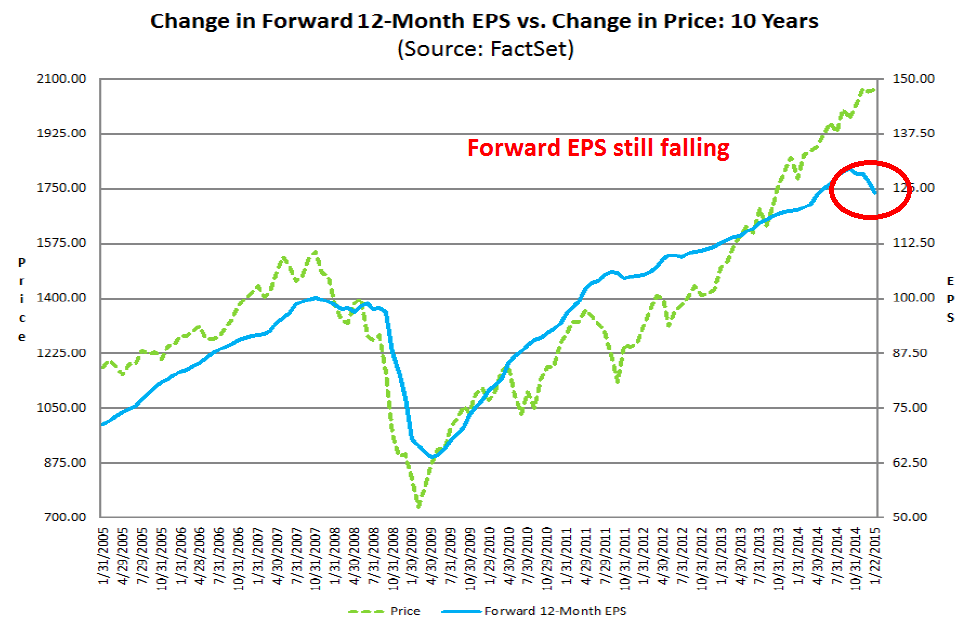

This would suggest that earnings growth going forward should also be very weak. In fact, we are already seeing this reflected in companies’ fourth quarter earnings reports and in the forward guidance they are now giving. Goldman Sachs reports that guidance is now the worst ever recorded. Forward earnings estimates are beginning to reflect this as they have been falling for almost as long as long-term interest rates have been:

Chart via Humble Student

Chart via Humble Student

From this perspective, it’s very hard to make the case that low-interest rates are a valid reason to be bullish on equities. It may be true that low rates encourage increasing risk taking when investors compare alternatives to the “risk-free rate” of the 10-year treasury bond. This is where the Fed’s interest rate lever and quantitative easing have obviously been successful. But at some point, plunging interest rates like we have seen over the past year, are a sign that earnings growth could be rapidly slowing if not turning negative, a development not at all supportive of risk assets.

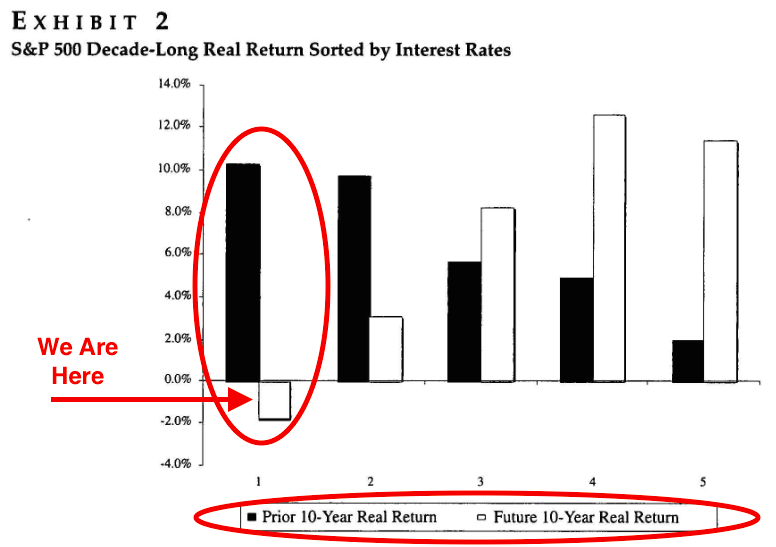

Historically, this may be represented by the fact that low interest rates have led to the worst forward returns for stocks. The chart below separates the market into five distinct buckets ranked by the level of interest rates. Bucket 1 reflects the lowest month-end 10-year treasury rates on record during the 1965-2001 period. It’s clear that the 10 year periods leading up to those low-rate environments were fantastic for stocks. The subsequent 10 years were not nearly so kind, as investors suffered losses after adjusting for inflation.

Chart via Fight The Fed Model

Chart via Fight The Fed Model

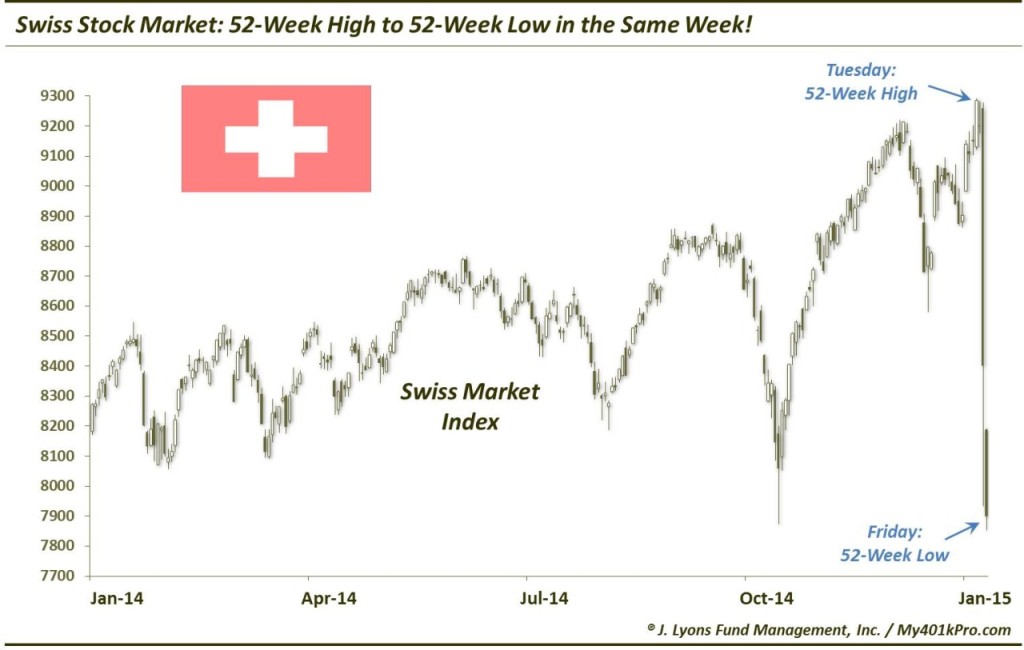

There is also recent evidence in other countries that the idea of low interest rates supporting stock prices is faulty. Just take a look at Switzerland. This Swiss 10-year bond yield is now negative. Based on the idea that low rates justify higher valuations, one could make the case that an infinite price-to-earnings multiple for stocks would not be unreasonable in comparison. But what did the Swiss stock market do while their long bond yield recently plunged? It also plunged!

Chart via JLFMI

Chart via JLFMI

The point is investors like to use low rates as justification for higher equity valuations. At some point, however, really low rates go from being benign to malignant for risk assets. No doubt low rates have supported risk assets in our markets for the past five years or longer. But the rapid decline over the past few months is now being reflected in company earnings. And investors may soon begin to question whether it still makes sense to pay record-high valuations in light of this.