Not so long ago I wrote, “this is probably the second worst time to own stocks in history.” However, when you look at the market a bit differently you can make the case that this could be THE worst time ever to own stocks.

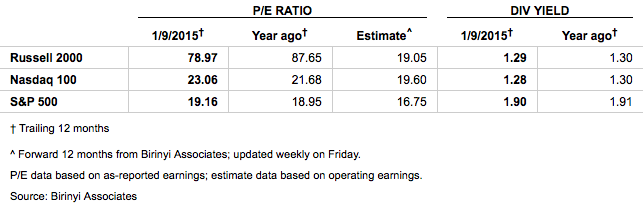

Most broad valuation measures are market capitalization-weighted simply because the major indexes are cap-weighted. The S&P 500, for example, currently trades at a price-to-earnings ratio of about 19. However, the p/e of the Russell 2000 small cap index is closer to 80!

Chart via wsj.com

Chart via wsj.com

This disparity between the two is hidden from the valuation discussion most of the time because it usually focuses on the stock market as represented by the largest 500 companies. When you look at the broader market, though, it’s clear there’s much more to the story.

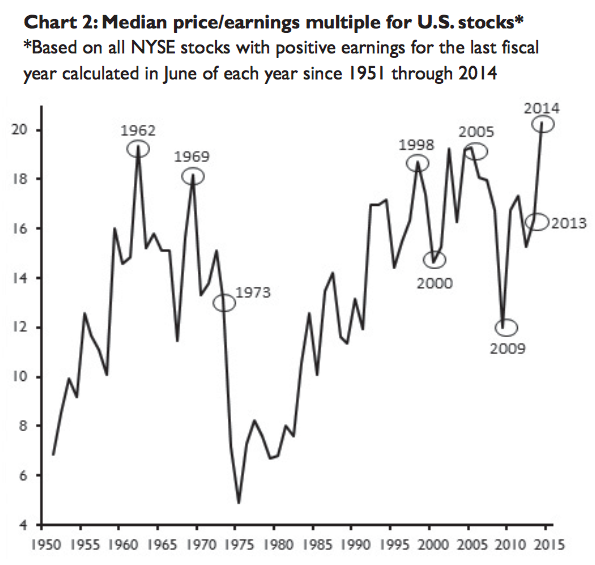

So how do we reconcile the small cap p/e that is off the charts with a large cap p/e that is elevated but not nearly as ridiculous? Looking at the median p/e (the valuation of the company in the exact middle of the pack) should do the trick. Fortunately, Jim Paulsen of Wells Capital has already gone to the trouble of putting this together:

Chart via wellscap.com

Chart via wellscap.com

There you have it: the most overvalued stock market of all time, based on median price-to-earnings. (For what it’s worth, Paulsen also demonstrates in the paper that on a price-to-cash flow basis stocks have also never been as highly priced as they are today.)

Here’s what I think you should take away from this. The first thing I think about when I see a chart like this is my potential reward versus the potential risk I’m assuming. The best possible situation would be for valuations to remain elevated for the foreseeable future. Then my gains should be roughly equivalent to corporate earnings growth, probably in the low to mid-single digits. However, in a worst case scenario, valuations return to the bargain bin and I’m facing steep losses (possibly 50% or more). All in all, I’m risking half my capital to make a single digit return.

The second thing I think about when looking at the chart above is my long-term rate of return is determined by the price I pay. If I’m fortunate enough to get a below-average price then over time I can reasonably expect an above-average return from stocks (10% per year or more). Pay a high price and I guarantee myself a mediocre return. Pay a record-high price and I’m essentially locking in one of the worst long-term returns in history (probably somewhere close to 0%).

Now I have to say that I believe price-to-earnings ratios are not the best way to value individual stocks or the broader market. There are other methods that are much more valuable for forecasting long-term returns like Warren Buffett’s favorite yardstick, total market cap-to-GNP. See “everything but the US stock market has already peaked” for my latest update on it and other indicators crucial to long-term equity performance.